A designer, urbanist, and social innovator, Liz Ogbu is an expert on sustainable design and spatial innovation in challenged urban environments globally. She is founder and principal of Studio O, a multidisciplinary innovation practice that works within communities in need globally to use the power design to catalyze sustained social impact. Liz’s projects include a design workshop at the Clinton Global Initiative Annual Meeting, Oakland Museum of California, and Pacific Gas & Electric. In addition to her practice work, Liz has served as an educator at several universities including UC Berkeley, Stanford, and the University of Virginia. She also frequently gives lectures about social and spatial justice, including her 2018 TED talk “What if gentrification was about healing communities instead of displacing them?”. We spoke with Liz about her work and how design impacts our culture and communities.

How do you believe design impacts our culture?

Artist and activist Favianna Rodriguez has said that “before there can be political change, there must be cultural change.” Design has the potential to render the invisible visible and bring pieces of our radical imagination to life. Meaning it can play a big role in defining what is culture and whose culture we value as well as shifting the cultural narrative. I think the question we should be asking ourselves is how do we leverage design with greater intention and accountability within the cultural landscape?

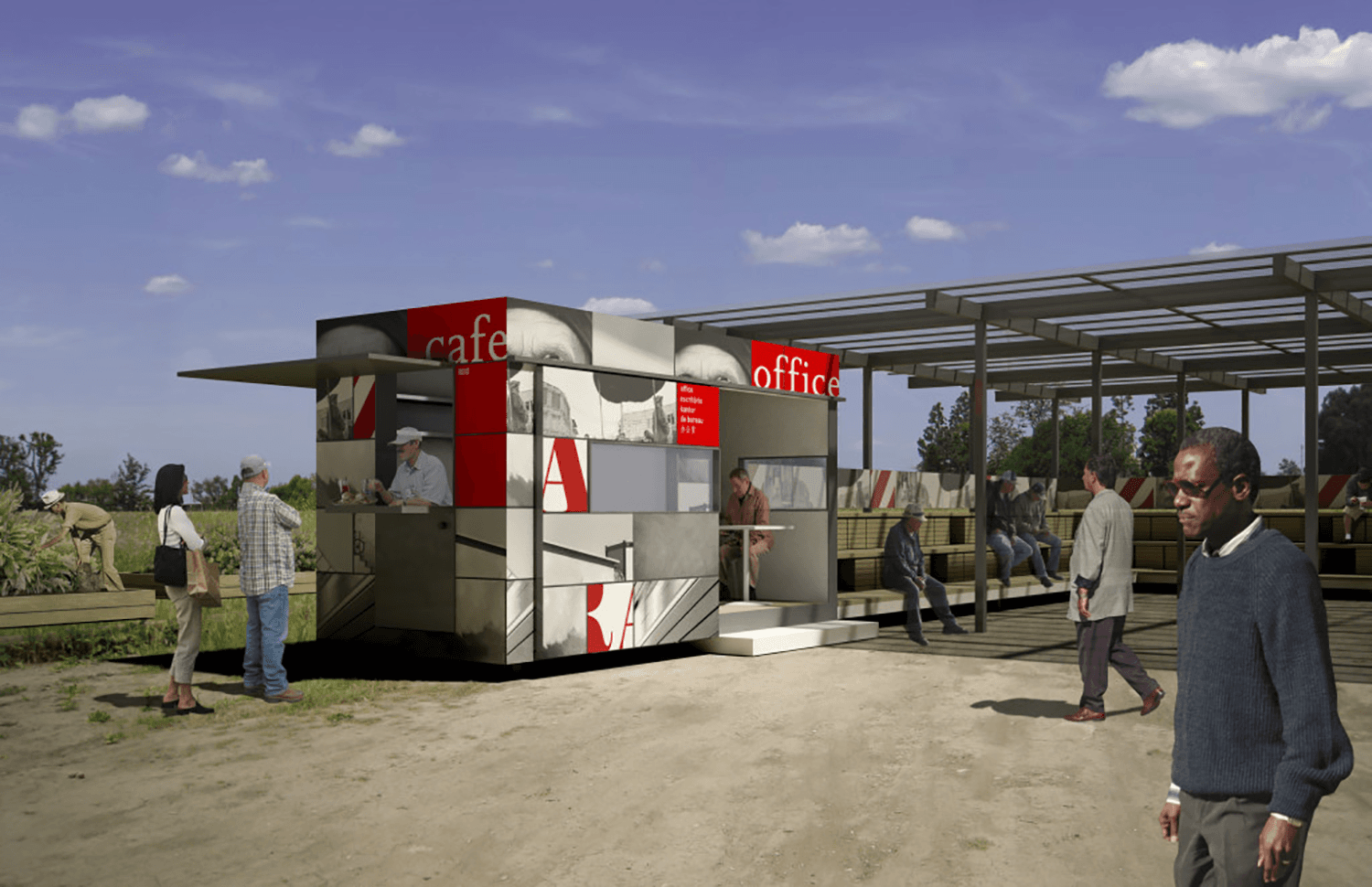

Day Labor Station concept by Liz Ogbu to accommodate some of the over 110,000 people in the U.S. who look for day labor work each day. The Day Labor Station was an innovative design and advocacy campaign that worked with day laborers across the country as clients and seeks to address critical issues of space, dignity, and community. | Source

What’s something that will always remain important in designing a space?

People. If we’re not being thoughtful about who we’re designing for, the context of their individual and our collective stories that brought us to this point, and the ultimate people-centered outcome that we’re striving for, then I’m not sure we’re engaged in more than a design exercise. That being said, other living things (animals, the land, etc.) should also be part of the equation.

How do you handle the community engagement process when designing in an area with a marginalized population?

So rather than saying “marginalized,” I prefer to say “historically under resourced” because it is more illustrative of the systemic nature of injustice, and it’s hard to address a condition if we don’t allow ourselves to take in the full weight of it. I also believe that we should think of principles of what I call intentional engagement as just good design. This is in part because those who have been forgotten or overlooked aren’t limited to one specific area, and in part because these practices are what we should deploy with any project involving people.

In general, I try to educate myself on what is the historical context of a place. Who has had access and who hasn’t. Who has had power and who hasn’t. And who is seated at the decision-making table and who isn’t and could benefit from me leveraging my own power, privilege, and creative agency to help get them a seat at that table. I also spend a lot of time in conversation with all project stakeholders, particularly those who have been most impacted. I don’t rely on community meetings as the only platforms for engagement, but rather seek out invitations to people’s homes, places of business, or wherever else they feel comfortable. And I think the two most important things to realize about community engagement are 1) the foundation of trust requires relational – as opposed to transactional connections – so figure out how to get to know people as people and how they can get to know you; and 2) community engagement is a marathon, not a sprint so be prepared to continually show up and be in dialog throughout the design and implementation process, even – and perhaps especially – during the tense moments.

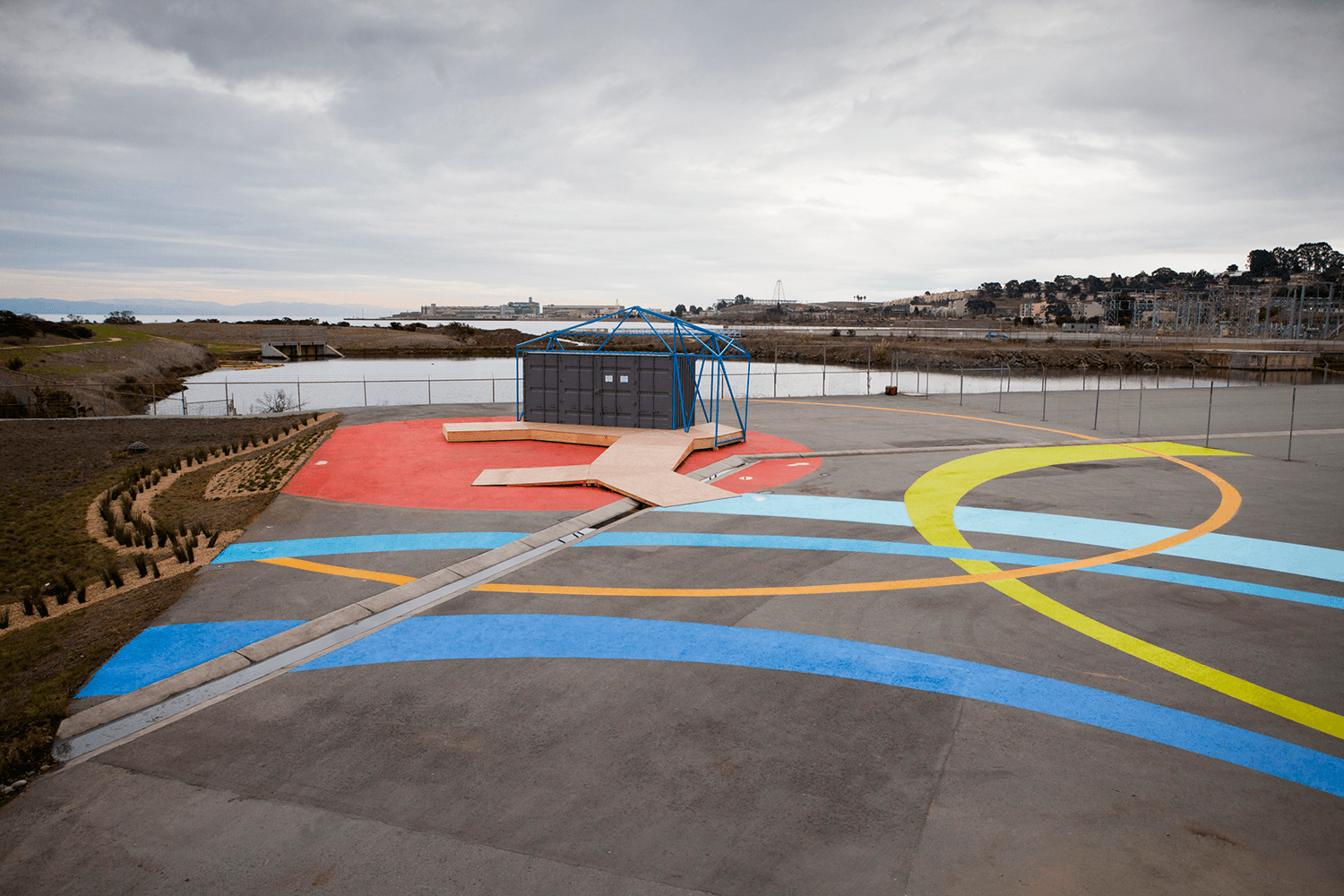

NOW Hunters Point was a former industrial site that included a power plant owned by Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E). PG&E worked with the project designers, planners, and the surrounding community to undertake a remediation process and return the space to the public. | Source

What inspires you when you’re in Chicago?

I have always been a city girl, and to me, Chicago is a city with a fascinating urban narrative. I embrace both the joyful and painful parts of its story, from its vibrant public spaces and rich architectural history to its segregated neighborhoods and challenged experiences with gentrification. Only by holding space for understanding the implications of both parts can we make our cities better.

Is there anything else you’d like to share with the Neocon community?

I think we’re at an interesting time in the world, and in design. I believe that there is no such thing as a neutral design. Understanding how we engage the complexity of this time is critical to the vibrancy and viability of our work. Don’t get me wrong; understanding how we as people and as designers engage issues such as power, culture, harm, and equity is totally intimidating but it is also completely necessary if we are to help contribute to a more just world.

See Liz present “Do No Harm: The Role of Design in Complicated Times” at NeoCon 2019 on Wednesday, June 12, 11 AM CDT. Register now.